Magical Appalachia

Botanist David Campbell enlists “citizen scientists” to help find rare plants and animals.

When David Campbell was growing up in Toronto, he says, “Appalachia sounded like a magical word to me.” He was the kind of boy who was always digging in the dirt to look at ants. But Canada had its limitations. He says, “Twelve thousand years ago, where I grew up was under a mile and a half of ice.”

Glaciers gave us the Great Lakes, but they weren’t exactly hospitable for living things. “Down here, you had plants growing and adapting and speciating for all that time,” David says. “Of course, wherever you have a great diversity of plants, you’ll have diversity of animals as well.”

On a wet November day, David chose a steep forested tract along the North Pacolet River, near Saluda, to talk about biodiversity. It’s the Melrose Falls property, part of a nearly-100 acre preserve owned by Conserving Carolina. It’s one of the richest forests in the region, he says.

Here, in the spring, wild ginger blooms near the ground, opening cup-shaped flowers that beckon ants as pollinators, ringed with pinwheels of hairy petals. There are flies that look exactly like wasps, yet aren’t. Sweet white trillium blooms more abundantly here than possibly anywhere else in the world, with thousands of the rare flowers carpeting the forest floor. Undiscovered species of insects probably live in the tree canopy, where scientists can’t easily study them.

David gestures at the rocks on the opposite side of the gorge. “There’s mystery in those cliffs still,” he says. He’ll do some climbing, but within limits. “I have a son, so I need to stay alive.”

David came to North Carolina to work as botanist in 1999 and never left. He and his 14-year-old son live in Hickory, but David is often in Polk County, walking along woods or streams or sometimes down on his hands and knees in the leaf duff, following the scent of a rarely seen flower that smells like cloves. This fall, Campbell published An Inventory of the Significant Natural Areas of Polk County, North Carolina, with no fewer than 127 rare or “watch list” plant species. But, to document the county’s most elusive flora and fauna, he needed to learn from local residents.

Citizen Scientists

Have you seen any black trumpet mushrooms? Or snail eating ground beetles? Do you know where to find vernal pools? Have you seen insects swarming over hilltops? Have you sighted any cerulean warblers?

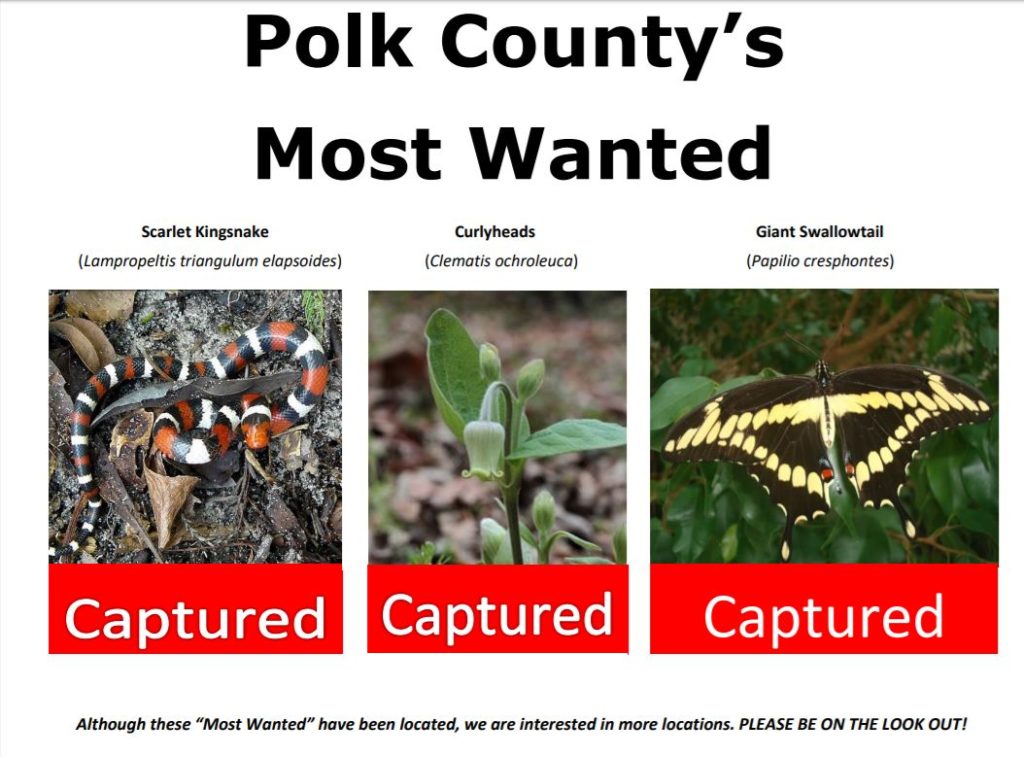

These are the kinds of questions that David and Conserving Carolina’s Pam Torlina regularly pose to the community, through a citizen science initiative called “Polk County’s Most Wanted.” Every month, they publish an article in the local papers, describing some rarity that people might be able to “capture” in Polk County in the coming weeks.

Pam, a conservation professional and accomplished naturalist, says, “We realized that if it’s just us out there looking for rare and unique species, we can’t cover a lot of ground—and a lot of it is private. This was a way for us to get the community involved and excited and also to be our eyes and our feet on the ground in places where we couldn’t be.”

Sometimes, Polk County’s Most Wanted features plants or animals that have been documented at just a few sites—could there be more? Sometimes, it features species that were recorded in the last significant botanical survey some 60 years ago. Or, David might be speculating, wondering if a species’ range could have stretched this far from the Ozarks or the coast or the boreal forests.

“We’ve gotten a tremendous response,” he says. “A lot of people have found many of the target species.” Out of the 71 “most wanted” challenges since 2011, 26 have been “captured.”

In one case, a landowner identified big bluestem, a prairie grass that may be a holdover from a different pattern of land use. Another landowner found mole salamanders, a thick-trunked salamander that is more common near the coast.

Landowners will sometimes invite David or Pam to come explore their property, where they nearly always find something of interest. People have shared plant collections that were passed down in their families. One Polk County native recalled that they used to see very large squirrels, which he described in clear detail, so David was able to add fox squirrels to the historical record.

“While I may have more specialized expertise in identifying this or that species, I’ll never know their property as well as they do,” David says. “Engaging landowners as citizen scientists also builds buy-in, because ultimately they’re the ones who are going to be stewards of that land.”

Protecting Natural Treasures

Polk County’s Most Wanted helped to springboard the much-needed inventory that David has just completed after seven years of field work. The study lists 32 areas that are important for biodiversity, with a focus on species that are in danger of extinction.

Previously, Polk was one of only five counties in North Carolina that lacked such an inventory. Conserving Carolina and the Polk County Community Foundation funded the study, and David, who volunteers his time on Polk County’s Most Wanted, also donated many hours for the study.

The inventory can help guide decisions by conservationists, government, and private landowners about places that are important to protect. You can find it online here. David will also be presenting his findings at Walnut Creek Preserve on Feb. 23, an event that is free to the public.

In the report, David explains that Polk County has an extraordinary number of species due to its dramatic changes in elevation, its varied rock types, its warm, wet climate, and its proximity to piedmont, mountain, and coastal ecosystems. The county is part of the Blue Ridge Escarpment, one of the most diverse areas in a region that the National Academy of Sciences has ranked as the #1 conservation priority for biodiversity in the United States.

As the climate shifts, it’s important to protect ecosystems like this, with numerous distinct niches, so vulnerable plants and animals can migrate to find the conditions they need.

David says that shifts in the climate may already be giving the forest a strange vibe. You see more plants flowering out of season—some of the redbuds, some of the blueberries. “You just don’t expect that in October or November,” he says. He’s seen beech trees dropping green leaves for no apparent reason. “Someone like me that watches this intensely, you make a note of it. I can’t attribute it to anything with the climate per se, but it makes me wonder.”

Some of the possible effects of climate change are less subtle, like the landslide that tore down a slope at Melrose Falls after sustained heavy rains this spring.

There are other changes, too. Across the road, kudzu is devouring the banks of the North Pacolet River. And paulownia trees are springing up in the preserve. It takes active management to control aggressive invasives like these—but it’s like weeding a garden. That way, every spring, native plants like wild bleeding heart, Jack in the pulpit, many kinds of violets, and carpets of trillium can continue to make the woods a place of wonder.

To David, it’s clearly worth it. “A place like this, it’s just a jewel in the crown. It warrants special attention.”

Related: Study Finds Extraordinary Biodiversity in Polk County

This article, by communications director Rose Jenkins, was published in the Hendersonville Times-News as part of our monthly “Stories of the Land” series.