What the River Wants

A floodplain restoration could help bring back muskie in the French Broad

Gigantic muskellunge—or muskie—have long made their home in the French Broad River. They’re a favorite of anglers who seek their chance to reel in the powerful fish, up to 50 inches long. But today’s French Broad is a challenging habitat for muskie.

It used to be that the river would spill over the land, lingering in wetlands or slackwater areas called sloughs. Muskie and other fish would swim into sloughs to rest and spawn. They’d lay their eggs on plants or woody debris and the fry would hatch in slow-moving water full of food.

By the mid-20th century, pollution had all but wiped out muskie in the French Broad. Today the river is cleaner and muskie have been reintroduced, starting in 1970. Still, nearly all of the muskie in the French Broad today are stocked fish. They start life in a hatchery, not the river.

“Why is that?” asks Scott Loftis, who grew up fishing in the waters around Asheville and now works as an aquatic biologist for the state Wildlife Resources Commission. “It’s a native species endemic to the French Broad—why?”

Observers report that the muskie are trying to spawn.

“They’re just not successful,” Scott says. “The eggs’ survival is not successful. The fry survival is not successful. Because they need slackwater areas.”

Over the last 150 years, water-soaked floodplains have been converted into productive farm fields. People use ditches and berms to separate water and land. But, that contributes to swifter flows in the river that intensify bank erosion. And if you’re a fish, the confined channel means fewer places to slip out of the current, which runs fast and brown after heavy rains. Muskie eggs get damaged by swirling soil particles—like being sandblasted, Scott says—or they get washed away. The fry that do hatch, face an upstream battle their first year of life.

Restoring a Floodplain

“Enter in Conserving Carolina,” Scott says. Years of conversations about the river’s missing sloughs led to an ambitious idea—to restore a floodplain back to its natural condition. Conserving Carolina learned about some land available off Butler Bridge Road near Fletcher, where Mud Creek flows into the French Broad. The fields there flood so often that the land is marginal for farming—but prime for floodplain restoration.

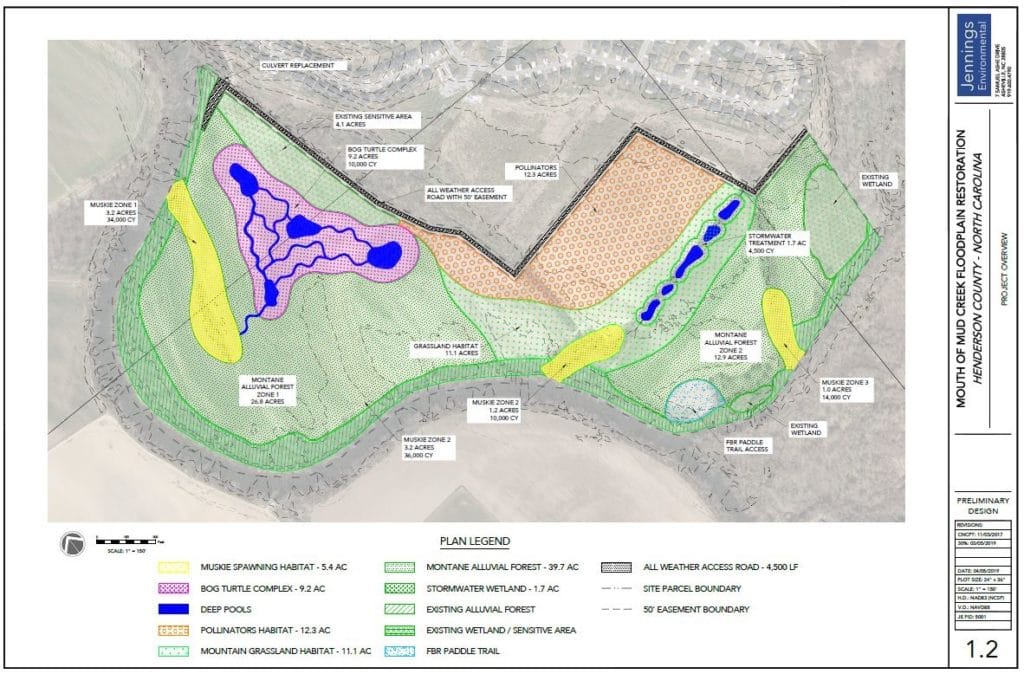

In 2015, Conserving Carolina purchased 103 acres at the mouth of Mud Creek. This year, work to restore the floodplain will get started. Plans include three sloughs where muskie can breed, a wetland that will support endangered bog turtles, reforestation along the river, and hilltop meadows for pollinators. Another wetland will capture stormwater runoff from nearby neighborhoods, improving water quality in the French Broad. Already, the site is home to the Mouth of Mud Creek campsite for paddlers, maintained by Mountain True. Future plans include walking trails and a potential connection to the Oklawaha Greenway.

Update: The restoration made front page news in the Asheville Citizen-Times in October 2020. And it’s part of a bigger picture for restoration along the French Broad River.

Many partners and funders are helping to make all of this happen, including Conserving Carolina, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund, N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources, N.C. Environmental Enhancement Grant Program, N.C. Natural Resources Conservation Service, N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, Fred and Alice Stanback, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Kieran Roe, executive director of Conserving Carolina, says, “I think this is the first time something has been tried on this scale in the upper French Broad River watershed—that we’re taking a property that has been impacted by humans and turning it back into a natural floodplain that will have all these benefits for the critters, the plants, water quality. Maybe this kind of comprehensive restoration is what we start to do more of. And maybe all that helps the French Broad River get healthier over time.”

Watching Swallows

After a heavy rain in April, the river swelled near the mouth of Mud Creek. Ducks swam in the fields and swallows circled, swooping and calling, over the wide, shallow water.

Watching the birds is relaxing, Scott says. He feels fortunate to have had experiences like this all his life—since he was a boy fishing with his grandfather. On the river, he says, “You see deer and ducks, you see beavers and all sorts of wildlife that are using this green corridor—it’s pretty amazing.”

For him, being an angler and being outdoors taps into something deep. “It’s hard to put into words and hard to even understand it yourself,” he says. “

“You just know that there’s something there that’s calling you and pulling you towards it. You just accept it and go with it, and maybe not ever understand it.” Or be like the swallows. “They’ve got it made,” he says. “They’re not asking those kind of questions.”

An Exciting Strike

Tim Boyer also grew up fishing in these mountains. But after he tried deep-sea fishing, he wanted something to match that excitement. “When I came back home from being in the Marine Corps, smallmouth fishing just didn’t quite seem as much fun as it did when I was a kid. Once I started getting into muskie fishing and actually seeing some action, that was pretty rewarding,” he says.

Now, Tim is president of the WNC Muskie Club, which brings together anglers who love to pursue the hard-to-catch muskie. The club members collect data to inform efforts to restore the huge fish in the French Broad.

With smaller species, a good day means you catch a lot of fish, Tim says. If you’re going for muskie, a good day might just mean that you saw some following your boat. Muskie are at the top of the food chain, so they’re spread out in the river. When they eat, they might eat something big and then digest it for days… so they might not be tempted by your bait.

“The challenge is part of it,” Tim says. “And when you do catch a really big fish, it’s an exciting strike. The fights are pretty quick but it’s pretty intense.”

When you spend a lot of time on the river, he says, you get a firsthand sense of how healthy it is. You see how many trees are falling over, as the banks erode. You see the river quickly go from clear to brown or red when it rains. If you see muskie, it’s a good sign. It means the river is supporting enough smaller creatures to support the giants.

The River and the Land

Scott followed his lifelong passion for fishing into aquatic biology, and now works in habitat restoration. A lot of his projects are smaller scale, like removing or widening culverts to improve fish passage. But the Mud Creek restoration is exciting, he says, because it brings so much together.

“A real primary function of a river and its floodplain is that connectivity and that exchange, back and forth,” he says. “But that exchange has been severed. So we wanted to restore that connectivity and that interaction.”

When the river floods, he says, it’s showing us what it wants to to do. And the ducks who choose that slower water are showing us. The swallows dipping for bugs are showing us. The river wants to slow down. It wants to flow over the land, and bring the fish and other creatures with it.

This article is part of our monthly Stories of the Land series which runs in the Hendersonville Times-News. These stories explore people’s connection to the land and the ways they give back to the places they love.