Saluda Railway Memories with Mrs. Pearlie Mae

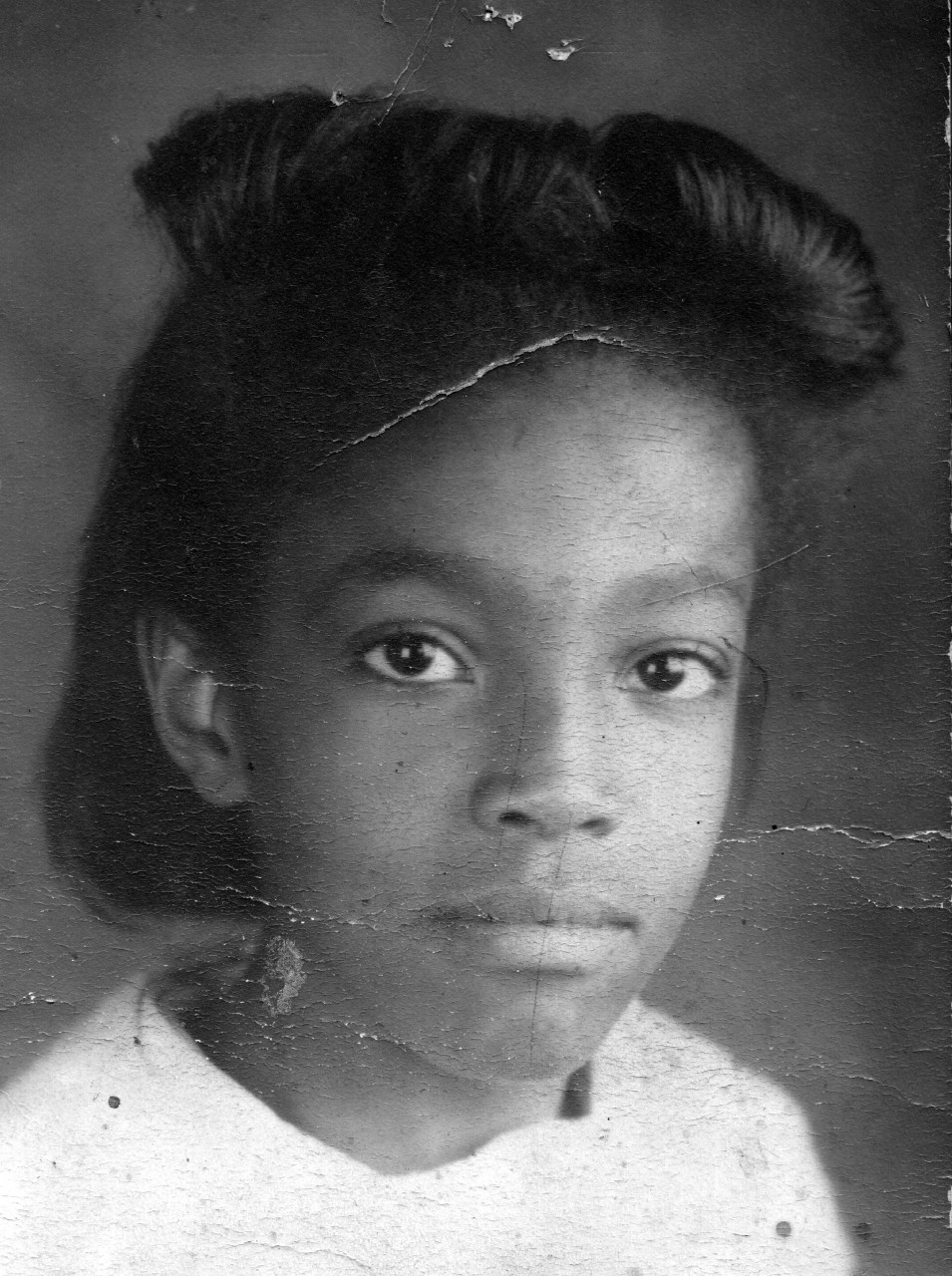

Renowned educator reflects on growing up along the railroad

By Carolyn Baughman

Light streamed through the windows of Mrs. Pearlie Mae Suber Harris’ home in Mauldin, SC. Glowing at the age of 87 in her butter yellow dress, she ushered her longtime friends Betsy Burdett and Carolyn Ashburn in for their regular visit. This time, they would be discussing memories of Pearlie Mae growing up along the Saluda Grade railway.

In the 1890’s many African Americans moved to Saluda to help work on the railroad. Later in the 1940’s, Pearlie’s family moved to Saluda. Her father, Reverend Lester Samuel Suber was to be the pastor of Saint Matthew’s Baptist Church. This was the first Black church in Saluda until the 1950’s when the Sullivan Temple was built by Pheobia Sullivan and her family.

As a child, Pearlie Mae’s father told her, “Always remember, you are a child of God just like everyone else and don’t you forget it.”

Growing up along the Saluda Grade Railway, Pearlie could hear the trains approaching near her log cabin home. When asked about life along the railway, she fondly recalls, “I loved living where the trains came up the mountains, that was fun.” She shared how the trains had to come up the mountain in sections because it was too steep for one whole freight train to make it up the hill. Once at the top, Pearlie vividly recalls the noises they would make as they re-locked saying, “I loved the sound of it. Unless you’ve heard it before, it is just amazing, [like] a rattle and an air dump. I wish children today could see that.”

Once the trains would start back on their route to Hendersonville, Asheville, and beyond, Pearlie remembers how her family would collect coal that fell from the locking and jarring of the trains. “That was part of our livelihood, using the coal that was left behind.” It was how they heated her home along with wood cut from their land.

Pearlie attended a school for Black children in Saluda. It was situated on land purchased in 1889 by the American Missionary Association for the sole purpose of providing land for schools for Black children in the South. A teacher came up from Tryon to teach the students.

The railway sometimes played a role in her walks to school. She recalls, “Some days, depending on who was on the street, we could walk directly through Saluda. But sometimes they would tell us we couldn’t so we walked along the railway tracks when there was no train.”

On those walks, she recalls that occasionally, “There were a few white kids who would throw rocks at us.” One day, Pearlie and her brothers were plotting a “rock revenge,” when their father came outside and said, “You’re not going to do that, you’re going to find another way to walk because I can’t walk with you every day.”

While growing up in Saluda, Pearlie earned extra money working for a white family named the Ogdens. One day, Pearlie was given $30 for her work. Pearlie returned home with the money, and her surprised father walked her back over to the Ogden home to inquire about the large sum. She recalls her father knocking on the door, taking off his hat, and politely asking Mrs. Ogden about the money. She replied “Oh Mr. Suber, do you know what she does to earn that money? She stands on a chair and cooks for us, she washes diapers, and she even irons our sheets. She deserved it.”

Pearlie’s father had required that when his children worked in the community, that half of their earnings went to the family fund. After Pearlie’s school closed down in Saluda due to black residents moving away to find work elsewhere, Pearlie started attending 9th Street School in Hendersonville.

Pearlie’s father later decided to purchase the former school building and would create a nice family home there complete with an outhouse, garden, chickens, pigs, cows and a horse. Her father turned to her one day and said, “See what your money has helped us do?”

Education would continue to be a powerful theme throughout Pearlie’s life. She graduated high school in 1953 and left Saluda to find work in Greenville. At that time, she was given the opportunity by Mrs. Simpson (of the Belks-Simpson department store chain) to attend Barber-Scotia College. Pearlie would go on to become a beloved teacher in the community for the next 39 years. She earned her Masters degree from Furman University, where she would also later receive an honorary doctorate. In 2020, Pearlie was also honored as the subject of a large-scale mural in downtown Greenville, celebrating diversity and education.

Throughout her life, Pearlie returned to Saluda numerous times and was a frequent guest speaker at Saluda School. She still has fond memories of life along the railway and made efforts to ensure her children had their own special railway experiences throughout their lives.

A generation later, the historic Saluda Grade Railway has an opportunity to become the Saluda Grade Trail, a proposed 31-mile mixed-use corridor connecting Inman, SC to Zirconia, NC.

When asked about the proposed trail, Mrs. Pearlie Mae shared, “It could be an access for so many people to enjoy a nice quiet trail that’s safe, and something that they can do with their children. So I hope it means a lot to the community.”

The Saluda Grade Railway has an untold number of stories just like Pearlie Mae Suber’s family along its route. This is the second in a series of articles about the local people whose lives are intertwined with the past, present, and possible future of the Saluda Grade Trail. See more Saluda Grade Stories.

For more information about the Saluda Grade Trail, visit saludagradetrail.org.