Choose Your Friends Wisely, Choose Your Enemies Wiser

Is privet friend or foe?

I am an absolute lover of plants. The exploration of the botanical world has led me to deep, wide and vast appreciation for our planet and all the life here.

There are a few plants though, that I, however, respect more so than love. I’m thinking of poison ivy, a plant that causes mild skin irritation for most people, and is also related to cashews and mangos.

I respect that eating too many cashews and mangos can increase the reaction or sensitivity to its plant cousin with its curious defense mechanism. But what of thinking of a plant as an enemy?

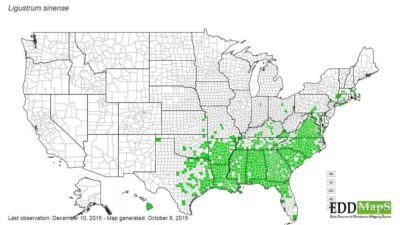

I have to say one does come to mind, privet (Ligustrum sinense), from the Asian continent. Privet is the evergreen shrub you’ve seen pretty much everywhere, imported as a hedgerow plant.

Privet very quickly spread throughout the southeast, displacing a great deal of biodiversity in a variety of natural communities – it has found a home in wetlands, fallow farms, sidewalk cracks, and it grows where other plants won’t (and all the other places plants will too.)

But I can’t be mad at a plant. It is only doing what it knows best to do, to make more plants of itself.

I can however be strongly displeased with some of the reasons we have an ultrafast global plant exchange, and be mad at the impacts on the southeastern United States ecosystems.

Think about it, if you – a living thing – were ripped up from where you were adapted to, plunked down in a strange place, wouldn’t you do all you could to survive, even thrive?

So I choose to respect this plant for its vigor, but none the less its presence here must be addressed.

The trouble with the plant is its displacement of existing biodiversity, forming a natural community described as a novel ecosystem.

No good/bad judgement, but it is truly new to the planet.

We do not understand how the novel plant’s effects will ripple through the living web of life there.

It is fair to say we only know a sliver of what makes ecosystems function, but we do know when an ecosystem provides reciprocity for stewardship: we feed ourselves, derive medicines, and cultivate gratitude for the land that we in turn give back vitality.

Mind that we as humans have evolved, learned and lived with ecosystems over deep time. (Sorry, here is your careful reminder –you, all that you care for and love, are all completely interconnected and interdependent with the natural world, just saying.)

In our modern, global-commerce world, new plants in old ecosystems are ramping up the speed of change. One of the possible outcomes of going too fast is well, crashing.

A biodiverse ecosystem thrives on long-evolved relationships, exchanging the sun’s energy in somewhat mutual (“fair”) transactions of growth, decay and passage through many kingdoms of life. Privet interrupts that cycle by taking advantage of many places in the exchange, and more homogenizes the landscape.

While I choose not to get mad at any one plant, I do choose to do something. We can remove it from the most endangered places, we can remove it from our public places.

We can demonstrate the need to steward the whole land, as an act of reciprocity for our life-giving planet. It’s what we’re born to do.

Torry Nergart is an avid adventurer, a local Brevard dad and spouse, and just happens to be conservation easement manager for Conserving Carolina, a calling that often puts him in a climbing harness, or waders, on a bike, or, yes, in a kayak, too, to protect the land and water we all love.