Harmony Around The Campfire

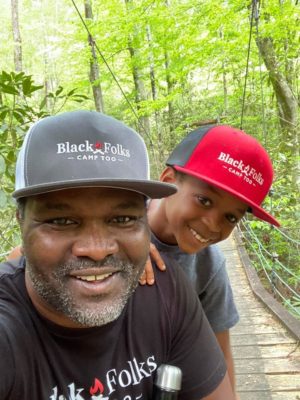

The founder of Black Folks Camp Too has an invitation for you.

As a sales executive, Earl B. Hunter, Jr. traveled a lot, away from his wife and his two young children. That was until his son, Dillon, who was seven at the time, confronted him.

“He said, ‘Dad, you keep telling me you’re going to take me to Mt. Rushmore, and yet you haven’t taken me. You always telling me to talk that talk and walk that walk. Well, I’m telling you to walk that walk,’” Earl recalls.

So, Earl told his son he’d pick him up on the last day of school and take him on the road. That summer, Earl brought Dillon on an epic tour of the U.S. He traveled to RV dealerships, convincing them to carry a unique product—Sylvan Sport pop-up campers. He and Dillon slept in the camper. Dillon learned to swim. They went to Mt. Rushmore, the Rockies, the Pacific Northwest, California.

“Then, something significant happened in Albuquerque, New Mexico,” Earl says. “I saw something that I hadn’t seen before. This big motor home pulled up. It was burgundy, beautiful. I looked over, I said, ‘That’s a black family! It turned out to be the only black family that we saw in 49 campgrounds, three months of traveling, 14,000 miles. And they were shocked when they saw us.”

In the campground, the two black families talked for hours. Earl recounts that the woman they’d met challenged him: “You say you’re one of the only black executives in the industry—why don’t you get black folks to go camping? Why don’t you do that?”

A Grandiose Idea

“I grew up in the hood. I grew up in the bricks,” Earl says. In the projects of Columbia, S.C., his mom raised six kids in a home without a father.

Earl was an athlete, driven to win. He didn’t have a dad in his life, but he had coaches. He calls his daughter Fuzzy, after a guidance counselor who served as a mentor—Marion Cooper “Fuzzy” Thompson.

Earl went on to play football at Georgia Military College and Appalachian State. After graduating, he joined the business world and traveled the globe, often to Asia to facilitate product sourcing. That line of work put him in touch with the Brevard-based company, Sylvan Sport, where he became VP of sales. That’s what first brought Earl to Transylvania County, where he lives with his wife, Tamika, Dillon (now 10), and Fuzzy (seven.)

He had plenty of time to think as he drove across the country in the summer of 2017, and the conversation in the campground sparked something.

“I had the grandiose idea that getting black folks in the outdoors, getting people around the campfire—I felt like the campfire could be this piece that brings a whole entire country together.”

Black Folks Camp Too

As a businessman, Earl saw an untapped market—to get more black people to buy RVs and pop-up campers, tents and camping equipment. In 2019 he founded a new company and gave it a bold name: Black Folks Camp Too. The company partners with the outdoor industry to market camping to black people—and welcome them into the great outdoors. This outreach includes the website BlackFolksCampToo.com, which offers information on how to camp, and Facebook and YouTube channels that show camping in a fresh light.

For example, the video where black men circle around a campfire at Black Balsam, playing music on their phone, dancing, and harmonizing.

Or the photo of two young men on a hiking trail shaking hands: a black Navy recruit and a white Army veteran who had met and shared their stories.

Or vacation pics of Dillon and Fuzzy playing in the ocean, near where their family camped at an RV resort.

Earl says Black Folks Camp Too is a company with a mission. “What we’re doing is monumental. What we’re doing is life changing. We’re changing mindsets. This is saying to someone, I’m going to show you something different. I know you may be scared and I know you may not have any knowledge, but I’m inviting you.”

That’s a mantra for Earl. There are three things we need to do to engage black people with the outdoors, he says: 1) Remove fear. 2) Provide knowledge. 3) Invite them.

You Are Invited

For centuries, wild places were often dangerous for black Americans. Runaways faced terror in the woods—captured in the film Harriet, when a black preacher warns the young freedom seeker, “If the slavers don’t get you, then the copperheads or the timber wolves will.” Lynchings took place in the woods. Parents passed on the fear of the country and the woods to their children, to keep them safe. For decades, parks and campgrounds were segregated. When that ended, many facilities for blacks closed down, but the places that were once reserved for whites still felt off limits. To this day, many black people feel uncomfortable going out to camping areas.

“We can’t go back,” Earl says. “I can’t go back and fix the horrific things that happened in the woods to black folks. But I can fix it now. I can give some knowledge. I can help remove some fear. And we can invite folks.”

And it’s not just black folks who get an invitation. People of all colors are invited to the campfire, the conversation.

Once we have camping in common, we can connect, Earl says.

“Why don’t we get black folks around the campfire with the folks who are already around the campfire? Now we begin to have this harmony, where people can talk around the campfire. We talk about our differences. And what we find is that our differences are more the same and our sames are not as different as we think.”

“I’m Out Here!”

This spring, Earl got invited to go camping. He had lots of experience camping in RVs, pop-up campers, and drive-up tent sites. But he’d never been backpacking, until some men—white guys—he’d met at an outdoor economy conference invited him to go with them to Panthertown in Pisgah National Forest.

“I knew I had to do it,” Earl says. It was a rugged 15-mile hike with heavy packs and a creek crossing. Earl’s boot split open, and his companions helped him repair it with duct tape.

“We talked the entire way,” Earl says. “I watched us get closer and closer. We started sharing more and more personal stories. We ate together, breaking bread. We helped each other put our tents up. We made each other coffee. We filtered water together. It was a bond of trust we were forming. I felt a sense of togetherness with them. Because in camping, you have to help people, and when you have to help people, color, gender, age—that goes away.”

They camped at a spot by a river, next to a waterfall, and built a fire in a ring of stones. That night, Earl woke up and got out of the tent. “I saw this beautiful shining light on this waterfall where we were camping and I was like, ‘I’m out here baby! I’m out here!’”

Coming off of that trip, Earl kept the energy going. He put out the call to a Facebook group: who wants to go camping? In the end, five black men, including his nephew and a guide, joined him to pitch tents at Max Patch—a grassy summit with panoramic views of layer after layer of blue mountain ranges.

Earl woke up in the pre-dawn light. It was so beautiful he cried—the tents with the men sleeping in them, against the backdrop of mountains at first light.

“I was like, this is beautiful. These guys had no idea this was here, and now they were sleeping in a tent, something they never thought they would do, on top of a mountain. And now, they can wake up and they can go tell their friends. Now their fear has been removed. Now they have some knowledge. And guess what they can go do now—invite somebody.”

This article is written by Rose Jenkins Lane as part of our our monthly Stories of the Land series which runs in the Hendersonville Times-News. These stories explore people’s connection to the land and the ways they give back to the places they love.